This brief excerpt from my draft book describes an incident I experienced at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. It introduces the chapter titled, “National Parks and Black Americans: Legacy of Exclusion.”

**********

Many of America’s national parks are located in urban areas. Among those “town jewels” is the National Mall in Washington, D.C. Although its name can be confusing (some out-of-towners ask where the department stores are), the National Mall not only is a separate unit in the National Park System, it’s home to several well-known monuments that comprise its memorial core. The Lincoln Memorial is one of those monuments.

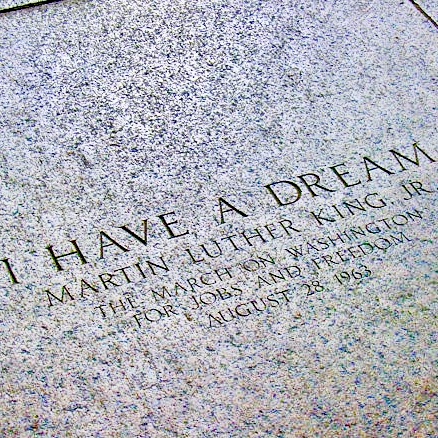

I visited the Lincoln Memorial often when I worked for the National Park Service in Washington. People reach it by climbing a broad stairway that affords a panoramic view of the Mall. But although millions visit each year, only a few notice an inscription carved into a step about halfway up:

I HAVE A DREAM MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR. THE MARCH ON WASHINGTON FOR JOBS AND FREEDOM AUGUST 28, 1963

Before the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial was dedicated in 2011, this modest marker was the only recognition on the National Mall of Dr. King’s momentous speech delivered from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. Yet despite its significance, most visitors walk right by or over the words, unaware that they are treading on the site of a singular event in the march toward American civil rights. I once conducted an informal experiment, standing by the inscription and pointing my camera down at it to see if this would attract curiosity seekers; but even that failed to draw any visitors.

One Saturday morning as I stood at the top of the memorial’s stairway, I noticed two women approaching the MLK engraving. One was White and the other Black. The Black woman appeared to be blind, but with the aid of her companion she knelt down and traced her fingers over the engraved words. As with my informal experiment, no other visitors seemed to notice what appeared to me to be a very meaningful connection. After a moment, the two ladies rose, exchanged a few words, then walked away.

In the years since, I’ve wondered about those two women and their stories. Where were they from? Why did they visit? Had either of them been part of the massive crowd on the National Mall on that historic day in 1963? Was I imagining a connection that wasn’t there, or was it deeper than I could possibly understand?

I’ll never know the answers to those questions, but they raise fundamental issues about the relationship between national parks and peoples of color. The centuries-long trauma of American slavery eventually led to the “I have a dream” speech at the Lincoln Memorial and the blind woman’s encounter with the King inscription. By physically touching those words was she connecting with an experience that few White persons can fully comprehend? If so, what does that say about how African Americans and White Americans identify with national parks?

More importantly, does it provide clues about how to reverse a long legacy of exclusion of Black Americans from the national park idea?