Climate change is affecting America’s national parks. Vegetation, native fish and wildlife, glaciers and lakes, even archeological sites and historic buildings, are all impacted. And those impacts affect people.

Winter recreation seasons shorten, summer seasons lengthen, wildfire and smoke make vacation travel difficult or dangerous. Hot temperatures kill or injure unwary or poorly prepared hikers. Some impacts, such as sea level rise, shoreline erosion, and melting permafrost threaten coastal and Alaskan structures, both historic and prehistoric.

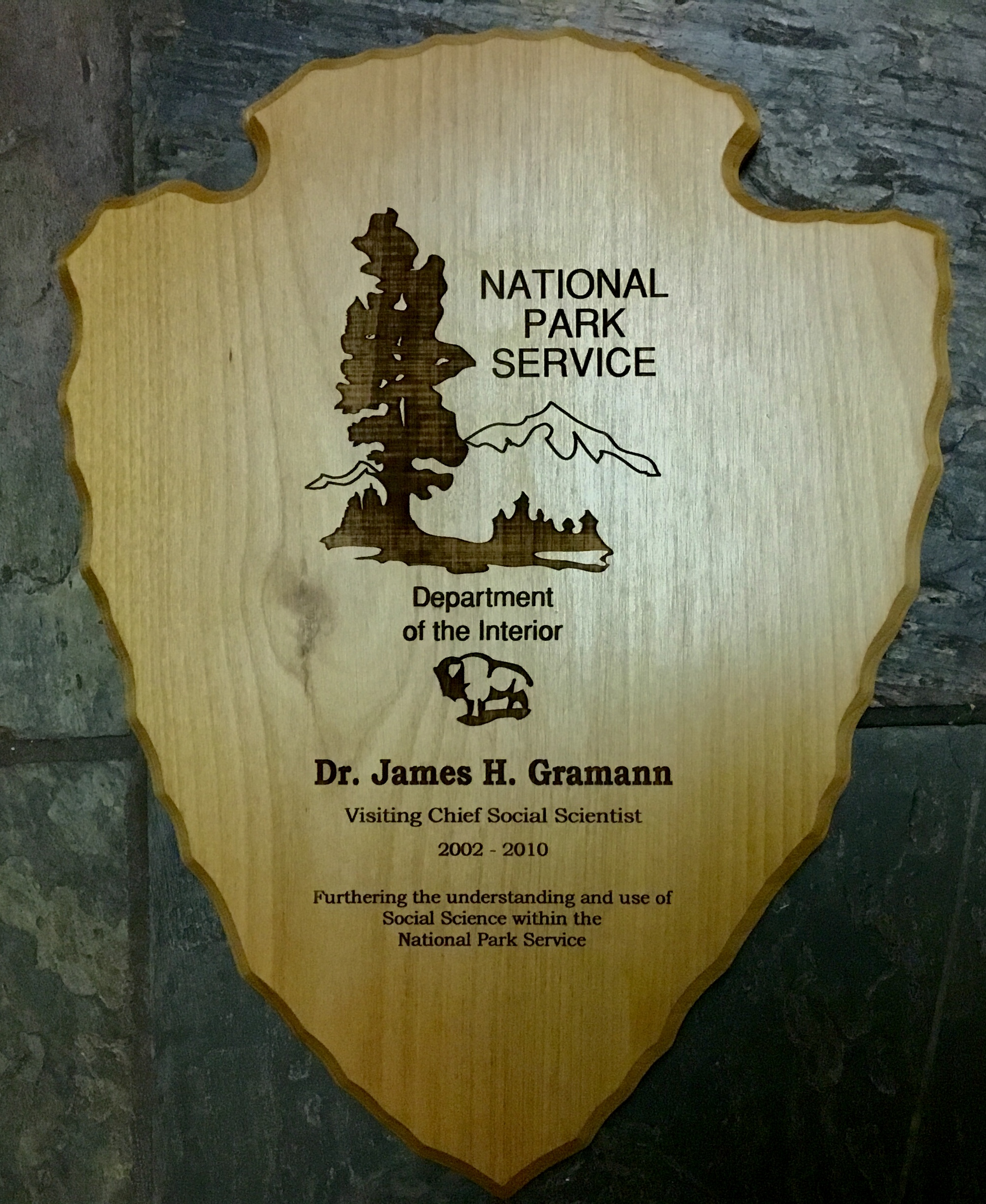

When I served In Washington, D.C., as the National Park Service’s visiting chief social scientist, I worked with university and consulting partners to conduct as many as 50 visitors surveys in parks each year. Those surveys had to be reviewed and approved by the Office of Management and Budget, part of the Executive Office of the President of the United States.

Then, as now, parks were concerned about climate change. But the issue was highly politicized. My time in Washington partly overlapped with the administration of President George W. Bush, whose policies down-played human-caused impacts on climate.

As a result, parks and researchers were not allowed to ask visitors questions about climate issues, even as those issues affected the parks’ management, their budgets, their ecosystems, and public safety.

Did visitors think climate change was a threat? Did they believe that human actions contributed to it? What kinds of changes in climate did they see as most important? What did they want to know more about?

Answers to those questions would be usable knowledge that parks could employ to guide interpretive programs and develop risk management strategies to protect park visitors. But they were forbidden. Any survey that included such questions would be “disapproved” by the Office of Management and Budget and never make it into the field unless the questions were dropped.

But the times, they are a-changing. Public awareness of the threats posed by our changing climate and its impacts is spreading.

The poem below has a history that reflects the shift in attitudes and policies towards climate. I began drafting it in 1999 during a faculty development leave at the University of Idaho a few years before I went to Washington, D.C.

My leave occurred during the winter. Needless to say, winter in Idaho is a bit different from what I was used to in Texas, where snow in my part of the state was a novelty that occurred every few years or so.

In 1999, debates over climate change were just a whisper. So when I began work on this sonnet, it wasn’t in that context. Instead, I was enchanted by the Idaho snow and, as my leave progressed into spring, I felt saddened when it began to disappear—saddened by the slushy streets and melting drifts that turned a winter wonderland into a sloppy stew. The poem reflected that sadness.

Originally, I titled the poem Last Snow. It was meant to complement an earlier sonnet, First Snow, that also was based on my Idaho experience. But as the years went by, and Last Snow remained unpublished, I tweaked it.

I began my work with the National Park Service in 2002. People were talking more about climate change by then, but there were still many climate deniers, especially in certain political circles in Washington, D.C. But the topic was moving to the forefront of national and international discussion, often under the label “global warming.”

So it occurred to me that my poem, rather than being a eulogy for a dying season, could be a commentary on a warming planet—thus, a new title, Warming Trend.

And I made another key change. But before I discuss that, here is the poem in its present form:

Warming Trend The end of snow—ethereal, frail as the final conscious thoughts of evening, quickening the quiet step away from winter’s neighborhood, diminishing. The surreal snow, its remnants sick with careless gluts of industry, ravaged while we slept, unraveling winter’s labor. Could its comfort linger, though this sad cascade to spring trickles from a shattered season, whispering “Let go”? Drifts of incandescence dim, betrayed beyond redemption, torn and tattered as we bleed the end of snow. James Gramann, unpublished

The second change I made occurs in the last line of the poem. Originally, it read “as they bleed the end of snow,” referring to the melting drifts. But the change to “as we bleed the end of snow” means something else entirely. It underscores the human role in climate change, a role that, in my poem, makes Earth’s climate bleed.

When I talk to others about poetry, I sometimes say poets sweat words. By this I mean that poetry values economy in wording, so that every word counts. Each word is painstakingly chosen for its meaning, its sound, and its rhythm. As a result, even the smallest word is vital. Warming Trend illustrates how changing just one of those small words can alter the entire meaning of a poem.