In the waning days of 2022, Congress added another unit to America’s national park system. The authorization of New Philadelphia National Historic Site, an archeological site in western Illinois, brought the number of established park units to 424.

I suppose there was a time in my youth when I aspired to visit every park in the system. But at some point I realized that even if it could be done (and many claim to have accomplished it), it would be a temporary achievement. Even if I managed the impractical—to add National Park of American Samoa, for example—within a short time a new unit would be authorized and my bragging rights to the totality of the system would be shattered. Is such an achievement, one that is so frequently undone, worth it? The reality is Congress creates new national parks faster than I can get to them.

Yes, I maintain a life’s list, just as some people compile life lists of the birds they’ve seen or heard. In fact, it’s quite a detailed list of the 347 official units I’ve managed to get to, camp in, lodge in, or work in over 50 years of married life. It’s not just a simple park list, but one that includes return visits to the same park in subsequent years. So, currently, it’s 24 pages long.

My list is arranged by state and—because I’ve had opportunities to visit national parks in other countries—by nation. But the international parks don’t count in my U.S. total of 344.

A surprising number of units in the National Park System are located in multiple states. I record visits to the Montana portion of Yellowstone, as well as the Wyoming portion, but visits to the same park in two states in a single trip still count as just one visit. And for purposes of my life’s total, Yellowstone only counts once, even though I’ve visited or worked in it 16 times.

My list also records visits to sites that aren’t officially part of the National Park System but cooperate in some way with the National Park Service. They don’t add to my life’s sum, but I consider them worth listing, with [brackets] around them to indicate they’re not “real” national parks. Most of those are affiliated areas, such as Thomas Cole National Historic Site in New York, or national trails, such as the Oregon National Historic Trail or the Pony Express Trail. The Appalachian Trail is the only national trail that’s part of the national park system, and I can claim to have hiked the width of it in multiple states.![]() But I only count it once in my life’s total.

But I only count it once in my life’s total.

My list includes the immediate family members who were with me on a visit; but with the kids now grown and launched, that’s usually just my wife and me. But I remain a proud papa when my daughter or son tells me they’ve visited another national park.

I still carry my park passport, a collection of booklets that goes back to 1986, and I still queue up at all the cancellation stations in a park to stamp my latest visit on its pages for use by some imagined scholar in the future who is researching obsessive-compulsive disorder. And if I buy a book in a park bookstore, I stamp that, too.

Early on, I developed rules about what counted as a “visit.” It couldn’t be a drive by, which is possible with the many parks that are comprised of a single historic building. I have to spend meaningful time in the park—at the visitor center or on a trail or tour, etc. In a very few cases, I’m forced to bend that rule for logistical reasons beyond my control. But I note that on my list. So I only “viewed” Buck Island Reef National Monument from St. Croix in the U.S. Virgin Islands. I was unable to arrange a boat to Buck Island during my limited time in the area, but I count it anyway. Deal with it.

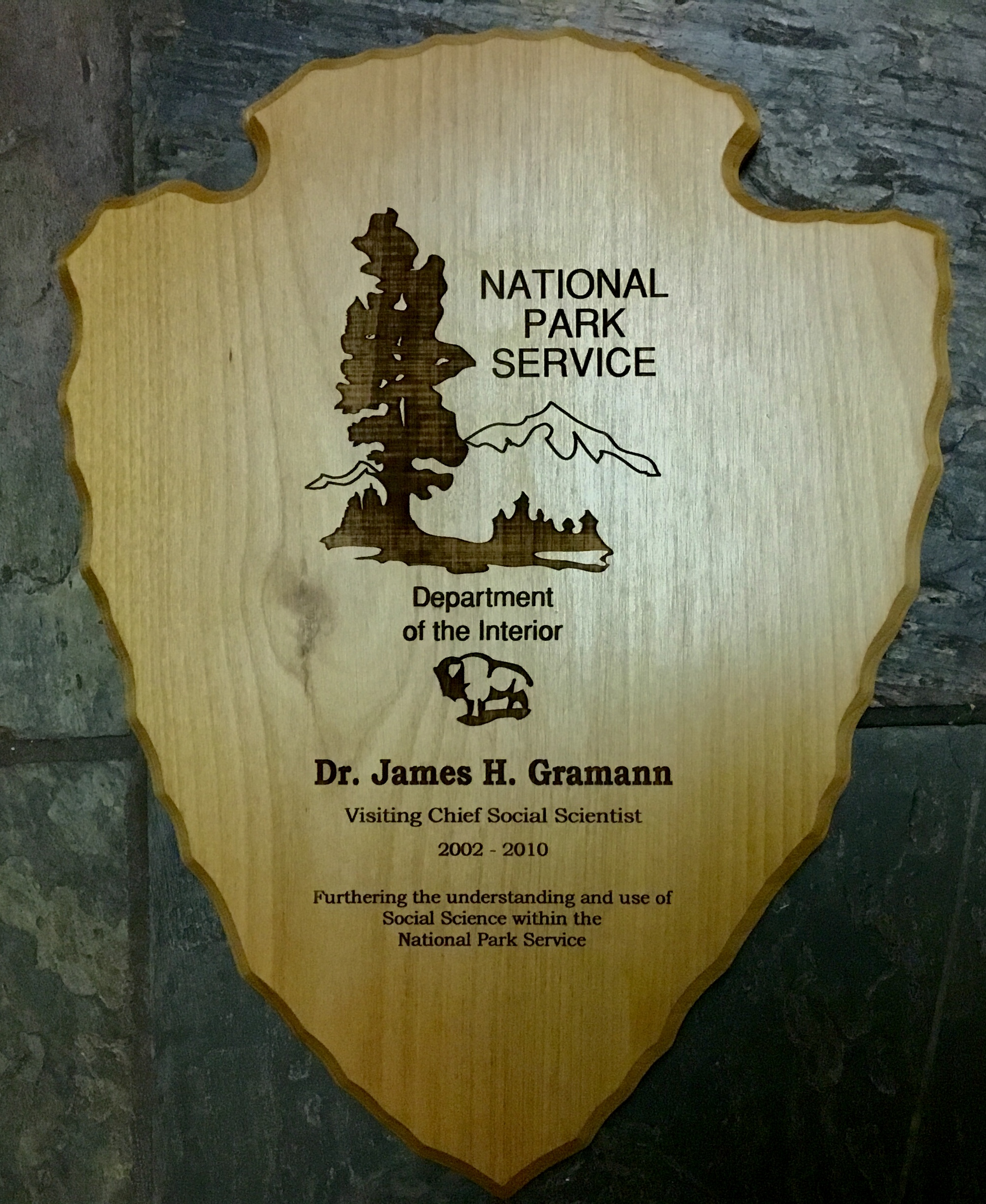

I’m at that point in my life where I realize that the number of maybe-next-years is shrinking and that my park list is moving towards its inevitable conclusion. In fact, I already know what that final entry will be. So my list may never include New Philadelphia National Historic Site. But that doesn’t bother me. Instead, I can peruse those 24 pages and reflect on what I’ve done, and not on what I haven’t. I can recall those parks I visited as part of a treasured family experience, those where I did my thesis research, those I worked in as a lowly concession employee, those where I served as a Volunteer-In-Park, those where I resided as a visiting scholar, and those where, as the National Park Service’s visiting chief social scientist for eight years, I contributed in some small way to their management or planning.

It’s a list worth keeping and a life worth living.